Licentiecontract opstellen

Een licentieovereenkomst legt de spelregels vast voor het gebruik van intellectueel eigendom zoals patenten of merken. Het gaat om afspraken over bijvoorbeeld exclusieve of niet-exclusieve rechten, financiën, controles en overdraagbaarheid. Het hebben van een contract is van belang voor het delen van kennis en producten zonder de eigendomsrechten uit handen te geven. Het wordt op maat gemaakt om aan specifieke behoeften te voldoen. Voor het laten maken van een licentieovereenkomst die past bij uw situatie kunt gerust contact met ons opnemen. Ook kunnen wij bestaande contracten screenen en suggesties doen ter verbetering.

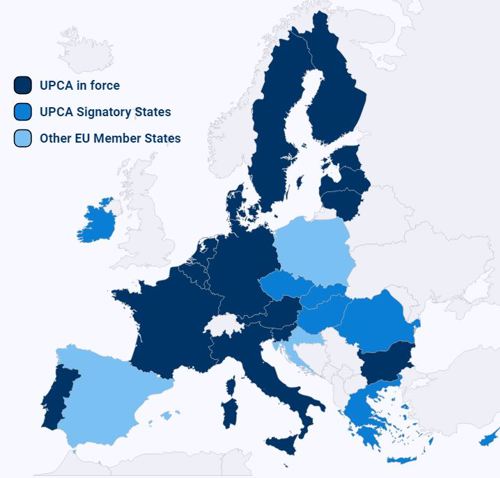

Unified Patent Court (UPC)

Het Unified Patent Court (UPC) systeem is een belangrijke ontwikkeling binnen het Europese octrooirecht, bedoeld om het verkrijgen en afdwingen van octrooibescherming in Europa te vereenvoudigen en te centraliseren. Dit systeem is opgezet om een uniforme benadering te bieden voor octrooigeschillen binnen de deelnemende EU-lidstaten, waardoor de noodzaak voor meerdere rechtszaken in verschillende landen over hetzelfde octrooi wordt verminderd.

Deelname aan Amazon Brand Registry

Het beschermen van intellectueel eigendom op online verkoopplatforms kan uitdagend zijn. Gelukkig verbeteren steeds meer verkoopplatforms hun beleid om dit voor merkhouders eenvoudiger te maken. Zo biedt Amazon via het zogenoemde Brand Registry merkhouders belangrijke tools voor merkbescherming, zoals proactieve maatregelen tegen inbreuk op intellectueel eigendom en onjuiste productvermeldingen. Ook kan het helpen om de klanttevredenheid te verbeteren en stelt het merkeigenaren in staat real-time gegevens te volgen over de bescherming van hun merk op Amazon. Voor deelnemers is wel vereist dat beschikken over een geldig merk.

Algemene bekendheid en vernietiging in het kwekersrecht

Het Hof Den Haag heeft in de uitspraak Strong Energy/Strong Strike van 3 oktober 2023 invulling gegeven aan het begrip 'algemene bekendheid' binnen het kwekersrecht. Niet uitsluitend registratie in het onofficiële KAVB-register, maar bijkomende feiten en omstandigheden brengen algemene bekendheid met zich mee. Daarnaast stelde het Hof dat de Nederlandse wetgeving die geen terugwerkende kracht toekent aan nietigverklaringen van kwekersrechten strijdig is met het UPOV-verdrag.

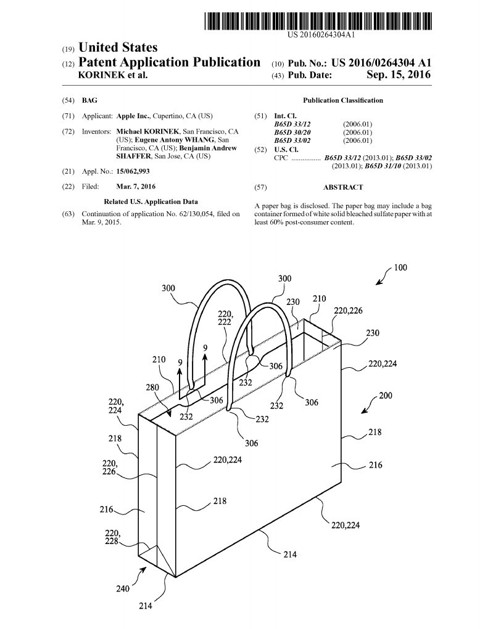

Apple draagtas

Apple's papieren draagtas is beschermd door een Amerikaans design patent. De tas is ontworpen door een team onder leiding van Jony Ive en gericht op duurzaamheid. Met het design patent wil Apple imitatie voorkomen. Biedt het modellenrecht in de Benelux en Europese Unie ook deze beschermingsmogelijkheden?

Beschikbaarheidsonderzoek

Voordat u overgaat tot het registreren van een merk (bijvoorbeeld van een naam, logo, slogan), kan het raadzaam zijn onderzoek te doen om te bepalen of het merk vrij is om te gebruiken en te registreren zonder inbreuk te maken op de rechten van anderen. Dit onderzoek is cruciaal omdat het helpt om mogelijke conflicten met bestaande merken te voorkomen en de kans op succesvolle registratie verhoogt.

Let op misleidende facturen!

Is uw merk, patent of model verleend en gepubliceerd? Dan zijn uw contactgegevens zichtbaar in een openbaar register. Helaas maken oplichters hier gebruik van om valse facturen, de zogenaamde "spookfacturen", te verspreiden. Enkele tips wat u hiertegen kunt doen.

Merken en rasbenamingen

In dit artikel duiken we in de tuin van merken en rasnamen in de plantensector. Het onderscheid tussen deze twee is belangrijk is om zowel kwaliteit als herkomst van planten te waarborgen. Het legt uit hoe merken consumenten helpen kiezen, terwijl rasnamen iedereen in staat stellen specifieke plantensoorten te identificeren.

Al een eeuw gebrandmerkt

Honderd jaar geleden zei Charles Strite vaarwel tegen verbrande toast in fabriekskantines en vond de broodrooster uit, een keukenrevolutie gestart vanuit ergernis! Van brood roosteren boven vuur tot een chic statussymbool met de eerste elektrische versie. De Toastmaster, gelanceerd in 1926, beloofde "You do not have to watch it - the toast can't burn" en werd een wereldwijd succes.

Grappen jatten op X verboden

Twitter (tegenwoordig X) beschouwt het stelen van grappen als plagiaat en een inbreuk op het auteursrecht, nu tweets auteursrechtelijk zijn beschermd onder de Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Dit beleid leidt ertoe dat tweets zonder vermelding van de originele bron verwijderd worden, ter bescherming van de creatieve inspanningen en de rechten van de originele grappenmakers.

Michael Jackson's patent

Michael Jackson is uitzonderlijk te noemen omdat er weinig tot geen andere artiesten zijn die zich eigenaar van een 'gepatenteerde' dansbeweging kunnen noemen. Hij bedacht een technisch oplossing om een dansbeweging mogelijk te maken.

Dwanglicentie

In maart 2017 wees het CPVO een verzoek voor een dwanglicentie voor het zwartebessenras 'Ben Starav' af, omdat niet aangetoond kon worden dat het openbaar belang geschaad werd. Dit besluit volgde ondanks het argument dat dwanglicenties kunnen worden verleend voor de bescherming van gezondheid of ter bevordering van de marktintroductie van bepaalde eigenschappen bezittend materiaal. Het CPVO benadrukte dat de voordelen van het ras 'Ben Starav' niet uniek waren en dat de afwijzing niet tot schadelijke gezondheidseffecten in de EU zou leiden, wijzend op de beschikbaarheid van alternatieve rassen voor vruchtensapproductie.

Geen vormmerk voor nieuwe Coca-Cola fles

De Europese merkeninstantie heeft het moderne Coca-Cola flesje definitief geweigerd als vormmerk, oordelend dat het geen onderscheidend vermogen bezit binnen de Europese frisdrankmarkt. Ondanks een marktonderzoek dat in tien EU-landen aantoonde dat consumenten de flesvorm associeerden met Coca-Cola, vond het Europese Gerecht dit bewijs onvoldoende voor registratie, aangezien niet aangetoond werd dat het flesje in de gehele EU als merk ingeburgerd is.

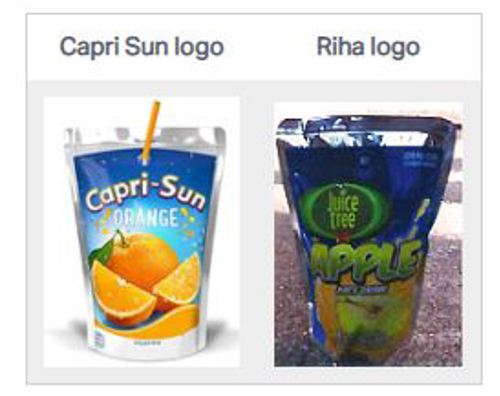

Capri-Sun versus Riha

Het Hof verklaart het vormmerk van Capri-Sun's iconische stazak nietig, door te oordelen dat de functionele trapeziumvorm, bedoeld om knoeien te voorkomen, niet voor merkbescherming in aanmerking komt. Een tegenslag voor Capri-Sun, waarbij creativiteit wijkt voor functionaliteit en nabootsing door Riha buiten schot blijft wegens de onvermijdelijke vormgeving voor functionaliteit.

Van flipflops tot virtuele virtuozen: AI en recht in het cybertijdperk

Van flip tot flop, we duiken van 1919's eerste elektronische geheugenstapjes met Eccles en Jordan's verrassende schakeling, naar het heden waar computers zelfs de muzen kunnen spelen, dankzij AIVA van Aiva Technologies. Deze digitale Beethoven heeft de muziekwereld op zijn kop gezet, erkend door SACEM, maar zit nog in een juridisch grijs gebied: is een AI een echte componist of niet?

Starbucks vs Coffee rocks

Na een hete juridische strijd die sinds 2013 pruttelde, heeft Starbucks in de arena van het Europees Hof van Justitie eindelijk zijn bitterzoete overwinning op Coffee Rocks geclaimd. Het Hof serveerde een frappuccino van gerechtigheid door te benadrukken dat gelijkenissen tussen de merken Starbucks' reputatie kunnen aantasten, ondanks geen direct gevaar voor verwarring. Het lijkt erop dat Coffee Rocks nu een slokje moet nemen van de realiteit dat in de wereld van merken zelfs een ster met een muzieknoot niet genoeg zijn om tegen de merkgigant op te boksen.

Toetreding tot UPOV

Egypte is per 1 december 2019 officieel het 76e lid geworden van UPOV, de International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, na in november de benodigde documenten te hebben ingediend. UPOV, opgericht in 1961 en gevestigd in Genève, streeft ernaar nieuwe plantenrassen te beschermen en daarmee de ontwikkeling ervan te stimuleren voor het welzijn van de samenleving, door ontwikkelaars een tijdelijk exclusief recht te geven op hun creaties.

Audit

Onze auditdienst is een professionele service die de nauwkeurigheid, integriteit en transparantie van de financiële verslaggeving en administratieve processen van een organisatie evalueert. Onze auditdiensten zijn gebaseerd intellectuele eigendomsrechten, met name kwekersrechten, waarvoor licenties zijn verleend. Licentienemers hebben toestemming verkregen om het beschermde product, ras of werk onder voorwaarden te gebruiken en te commercialiseren, bijvoorbeeld tegen betaling van royalty. Met een audit wordt gecontroleerd of de royalty correct wordt afgedragen en ziet u erop toe dat de voorwaarden van het licentiecontract worden nageleefd.

Max Verstappen geklopt door Picnic

Picnic hoeft geen schadevergoeding te betalen aan Max Verstappen voor het gebruik van een lookalike van de F1-coureur in een reclamespot.

Champion vs Chempioil

De oppositiekamer van het Europese Bureau voor de Intellectuele Eigendom (EUIPO) boog zich in oppositiezaak (nr. B 1958266) over de vraag of er verwarring te duchten is tussen de beeldmerken "CHAMPION" en "CHEMPIOIL". Beide merken werden in hetzelfde territorium gebruikt voor hetzelfde product, namelijk motorolie. Een duidelijk voorbeeld van merkinbreuk, of toch niet?

Vrijwaringsonderzoek

Een vrijwaringsonderzoek, ook wel Freedom to Operate (FTO) genoemd, is een juridische analyse die wordt uitgevoerd om vast te stellen of een bepaalde activiteit, zoals de ontwikkeling, productie, verkoop of het gebruik van een product of dienst, inbreuk maakt op de intellectuele eigendomsrechten van anderen. Onmisbaar voordat u aan de slag gaat met het lanceren van uw product.

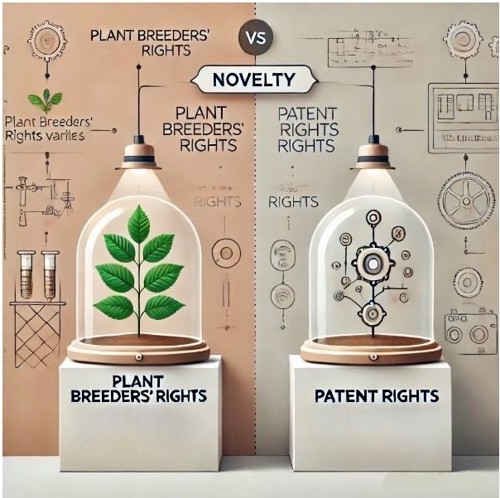

Kwekersrecht versus Octrooirecht: Wat zijn de verschillen?

Dit artikel bespreekt de verschillen tussen kwekersrecht en octrooirecht in Nederland. Het octrooirecht biedt bescherming aan door mensen ontwikkelde uitvindingen, zoals nieuwe technologieën, die gedetailleerd beschreven kunnen worden en waarvan de nieuwheid vervalt bij openbare bekendmaking vóór de aanvraag. Kwekersrecht daarentegen beschermt nieuwe plantenrassen, die minder voorspelbaar zijn en waarvan de nieuwheid enkel verloren gaat als het ras voor commerciële doeleinden toegankelijk wordt.